A review of Middlemarch

Middlemarch is a novel in eight volumes, published in 1872 by George Eliot. It focuses on the lives and challenges of an eclectic ensemble cast, who live in a small town in England in the early nineteenth century. It is an excellent book, and it is recommended that anyone who has not done so already read it as soon as possible. As a public domain work and classic, it should be available at your local library and bookstore, as well as project gutenberg.

Considering the technical aspect, the prose is engaging, engrossing and manages to use competent language and sentence structure to bolster the text. The vocabulary used is competent, allowing for more extravagant words while not descending into overly purple prose. The overall construction of the work is well done. Humor is used sparingly, and characters are questioned, but not judged, regardless of their actions. Sometimes, the prose lays bare the flaws of the characters for the audience to question, which is an effective way to avoid preachiness that many works fall into.

The narrative itself is excellent, and is standout amongst many of its contemporaries. While it is somewhat limited by the setting and concept, it is enticing, engaging and evocative. It is unique in being very un fantastical. Most stories in this time, and even today, even if they take place in a realistic setting often have the characters go through events that strain credulity. Middlemarch has things that happen to characters without their foreknowledge, but these are always due to their past actions. Of course in reality, you can be affected by something you did not cause, but many stories have characters go through events without them having any control over their circumstances. This is not the case in middlemarch, and there are no deus or diablos ex machinas.

Please be warned of spoilers in this section.

The book follows multiple characters through a few years of their lives. In the book these interleave, but I will summarize them separately for convenience.

Dorothea is a young orphan woman who is enamored with a much older man, and the prospect of serving his ambitions. and marries him, against the advice of her well wishers. These consist of her sister Cecilia, Sir James Chettam, a prospective suitor, and her bumbling and sexist, but benevolent uncle, Mr. Brooke. Chettam helps Dorothea build cottages for the poor in the community, and Dorothea has a deep yearning to be part of something important and improving the world.

The man, Mr. Causobon is frail, selfish and abrasive, with delusions of grandeur, and he brushes off Dorothea's attempts to be of service to him. She starts a friendship with his ward and cousin, Ladislaw, who finds Dorothea enthralling. Causobon is jealous of the younger man, despite not holding any idea of infidelity, and on his deathbed, bars Ladislaw from marrying his wife, and ensures she would lose his property if such an event takes place.

Fred Vincy and Mary Garth have been childhood friends, and are in love with each other. Fred went to college to study for the clergy, but Mary thinks that he would be living a lie preaching.

Fred has a gambling debt, and attempts to wrangle money (though he does not explicitly ask for it) from Peter Featherstone, an uncle to both Fred and Mary by marriage, to pay it off, after acquiring a line of credit from Mary’s father, who cannot pay it. Peter asks for a letter in writing from another one of Fred's uncles, Bulstrode, to certify Fred’s good standing. Bulstrode is an irascible, religious merchant who is one of the most politically powerful people in Middlemarch, and he alleged that Fred exploited his relationship with Peter, who would inherit him to his will, on credit. After Fred’s father intercedes, he relents, but the money is less than what Fred needs. Fred attempts to retrieve the rest of the money in some other manner, but he fails, and Caleb Garth has to fork over the cash at great personal loss.

Tertius Lydgate is a doctor who studied in Paris, and had a traumatic experience with an infatuation. In arriving in Middlemarch he aims to make a name for himself and revolutionize the methods of medicine in the town, which relies heavily on overprescription of drugs. He wishes to work for a new hospital and apply his techniques there, but Bulstrode funded the building, and he demands that Lydgate vote to certify a clergyman of his choosing to work for the hospital, and to cave to a more spiritual oriented method of healing. After being antagonized by his older colleagues for his unorthodox methods, Lydgate acquiesces.

Rosamond Vincy is bored and uninterested by the town’s male population, but quickly falls for the charming and handsome Lydgate, who is related to nobility. Lydgate finds her charming, but is unwilling to enter into marriage, and breaks off their acquaintance, but after Rosamond expresses her feelings, he makes her an offer of marriage.

Fred Takes ill, and is healed by Lydgate. Mary works for Featherstone, who is on his deathbed. Dying, he asks her to destroy a will he placed in a safe, but she refuses, fearful of legal reprisal. Peter dies, and it is revealed that he wished his estate to be transferred into an almshouse. If Mary had destroyed the will, Fred would have inherited the majority instead. Fred makes to take the clergy examination, but after passing, he is guided by a friend to listen to his heart. He takes up employment with Caleb Garth, who manages properties, and finds himself married to Mary and in the stewardship of the Featherstone estate, which passes through Bulstrode’s hands during the course of the novel.

Bulstrode meets an old acquaintance, a scoundrel called Raffles, who reveals an unsavory detail about his past. Meanwhile, Lydgate spent beyond his means to reward himself and Rosamund with a lavish life, and following a tragic miscarriage, finds himself in debt, which strains their marriage. Bulstrode is revealed to be the cause of Ladislaw’s mother’s misfortune, and Raffles takes ill, before telling the secret to Caleb Garth, who is discreet. Lydgate attempts to save his life at Bulstrode’s behest, but the latter lets Raffles die of negligence after disobeying the doctor’s instruction, and pays off the multifarious debts Lydgate had. However, Raffles had tattled to other men besides Caleb Garth, and the two men find themselves ostracized by the town.

Ladislaw gets a job working for Brooke’s political paper, and supports the latter’s bid for election, but this goes poorly. After Causobon dies and his will is revealed, he leaves Middlemarch, but his heart pines for Dorothea. Chettam and Celia marry and have a child. Chettam is opposed to Ladislaw, but his sister-in-law is not perturbed. Dorothea, who hears of Lydgate’s predicament, intercedes for him, and the latter refunds Bulstrode. Chettam is vexed by this. Ladislaw returns, having solidified his love for Dorothea, but the latter is found in a compromising position with Rosamund which causes a misunderstanding between him and her. After hearing about what Dorothea did for her husband, Rosamund explains Ladislaw, and he and Dorothea have a romantic reunion. Ladislaw marries her, and becomes an MP, while Dorothea works on improving the status of people alongside her husband.

There are many aspects of the narrative that this summary glossed over and did not elaborate on, as well as themes and concepts that permeate the text, such as the discrimination Dorothea faces and the parallels between the leads. Reading the story would be something that would be recommended to any adult. Even with foreknowledge of the story, there is still a lot to discover.

From an artistic point of view, middlemarch, despite following a set of semi-aristocrats, feels remarkably poignant in highlighting many issues that are commonly faced by humans. Dorothea’s regret of her naivety and dealing with disillusionment, Ladislaw pining for a woman he believes he can never be together with, Fred disappointing people he cared about and Lydgate’s money troubles straining his friendship. Regardless of social status, class, wealth or culture, most people will encounter events similar to the tribulations faced by the characters in this book. Art often seeks to express beauty, but in some forms, that is not the only aspect of art worth paying attention too. It often seeks to encapsulate the human experience as well, and at this, middlemarch succeeds. Characters often encounter challenges that mirror each other. Fred and Lydgate both have financial troubles. Lydgate and Dorothea both are stuck in marriages that differ from their fantasies. Ladislaw and Fred are both in love, but their beloveds seem so far out of reach. The duality of this, as well as how differently these trials affect the protagonists lend itself very well to depict a picture of modern humanity. Dorothea’s marriage is analogous to so many decisions that many of us have made or will make, entering a relationship, moving to a new country, getting a new job, and realizing that.. It was not what you thought it was. Fred shows how our mistakes hurt others, and that we may have to make tough choices to redeem ourselves, even if we avoid punition. Lydgate shows the effect of challenge on our family and how, even innocuous choices, if undertaken blindly, can harm us, whereas it can be argued that Fred and Dorothea knew what they were getting into, and were warned to desist.

Two characters however stand out among the rest. While the main cast deal with the fall back of honest mistakes, this duo represents the consequence of an absence of empathy. Casaubon and Bulstrode are central to the plot. In some ways, they can be considered the antagonists of the novel, but they are also well illustrated as people with their own lives, feelings and motivation, and Eliot invites us to feel empathy for them, despite them seemingly lacking this resolve for others. Unlike contemporary villains like Heathcliff in Wuthering Heights, Glyde and Fosco in The Woman in White, or Luzhin in Crime and Punishment, the duo are not cartoonishly evil. They do not wish to cause misery, and their crimes are not overtly malicious. They just lack empathy.

Causabon may be considered to be the less evil of the two, but unlike Bulstrode, he lacks any awareness that what he is doing is harmful. He does not comprehend why Dorothea feels that she has to help him, or shows interest in his task. He does not understand why she feels sorry for Ladislaw, why she wishes to build cottages, why she wants to do something or why she gives him praise for what he views as a formality in bankrolling his cousin. Therefore he remains incognizant of his wife, viewing her as nothing more than set dressing that can communicate. He refuses to communicate with her, becomes indignant if she so much as voices a question regarding his conduct and his work and tries to control her actions beyond the grave, unwittingly jeopardizing his life’s work in the process. There can be two considerations for why he does this. The society he occupies does not register his actions as sinful, illegal or immoral. Even today, it would be unlikely that he would face repercussions for his actions. Still, the harm he caused Dorothea, in both life and death, is tangible. The other reason, which compounds with the first, is that he lacks empathy. He does not understand Dorothea. He does not care for her.

Mr. Brooke is the one of the other characters, who, besides Casaubon, is openly sexist. He openly denigrates women and their choices in front of his two nieces. However, despite this belief, which is reprehensible, he does care for them. He expresses concern for Dorothea marrying Casaubon. He may not be able to read their minds, and his lodging of Ladislaw causes great consternation to Chettam, but he also is somewhat perceptive of their feelings, and shows compassion, even when he cannot understand what is going on. Causobon lacks both, and only cares about himself. Even on his deathbed, he does not understand why his actions are bad. Eliot was of course commenting on the deep rooted sexism in her time, and the time of Dorothea. Middlemarch was set about 40 years before when it was published, if it was released today it would be set in the 80s. Social Commentary aside, it also highlights how not extending our empathy to others can be harmful, even in a scenario where we are not negatively affected. Eliot extends her empathy to Causabon at a time when most readers would hate him, and doing so, shows a bit of him within us. Of course, most people, at least today, should not be so callous, but even the best of us, can fall victim to this. The events of human history, past the time Eliot lived, and even today, show this. Most of us will not murder or torture others, but any of us can disengage our empathy to other people.

Even with his lack of empathy, Causobon fails again when he exhibits jealousy regarding Ladislaw’s friendship with Dorothea. Compassion too, is important, even when you cannot understand how someone thinks or operates, caring for their wellbeing, even in a flawed manner, and being open to criticism will alleviate this. He fails in this regard, and fails further in communicating his thoughts effectively to Dortothea. When they first develop affections for each other, she is enamored with his explanations and expounding of his work and topics related to it, which appeal to her ecclesiastical inclinations. For Causobon, a young woman paying attention to, in his eyes, topics of deep import is something that gives him great rapture. Their intentions do not seem to delve too deeply into the carnal realm, even when they are married, and he outright rejects the implication of infidelity, which, while admirable, does not absolve him of his actions. I earlier stated that Causobon thought of his wife as set dressing, but it would be more accurate to say he treats her like a cheerleader, someone who cheers him on and supports him, but who cannot help in the nitty gritty of his work.

Causobon’s actions lead to his downfall, both in the mortal realm and the afterlife. He overworks himself, and does not listen to Dorothea’s advice to reexamine the importance of his work, in the context of recent developments in the same field. He does let Dorothea help and teaches her some of the languages he is working on eventually, but his actions lead him to contracting an illness that would kill him if he did not stop. His lack of empathy stops him from making meaningful relationships that would serve him after he cannot work on his project, and he throws himself back into it. Eventually, some change, from Dorothea’s perspective, happens, and he dies. She feels regret and sadness at the possibility that she will have to labor to complete Causobon’s work, that she knows is futile, but resolves to do it. Causobon, however, is telling in his last will. He prohibits Ladislaw and Dorothea from marrying. This was not something that either, at that moment, planned to do, and he sealed their fate, as well as his. He did not care for Ladislaw, or consider his wife’s feelings on the matter, and in the end, his name was forgotten, and all he had would rot, with his wealth benefiting no one. Featherstone’s will revealed a similar issue, and he also died with his remembrance in jeopardy. But, in the end, his action, or his belief, ensured that his will, in truth, at least, was carried out.

Bulstrode, the other antagonistic entity in the book, is similar, but his sin is, rather than a lack of understanding of right and wrong, an unwillingness to act on it. He knows what he is doing is wrong, but he still does it. He tries to rectify this with penitence, but, in the eyes of God, or in this case, George Eliot, penitence, without an attempt of rectification leads to misery. He marries a woman who lost her daughter, and hides the latter’s existence from the former to acquire wealth. It is notable that he does not do anything illegal, but like Causobon, it is still immoral. Unlike Causobon, this is considered poor in the terms of their contemporaries as well

Bulstrode seems to be capable of empathy, but he frames his understanding more on the concept of morality rather than understanding. He is self pitying, and attempts to frame everything by the ironclad rules of anglicism, or at least his understanding of it, and he does not extend to others the same liberties he gives himself, in renouncing their sins. In his case, its not his understanding of right and wrong that is the issue, but the why. It is more complicated than that, of course, as he does not change, but rather behaves strictly to circumvent his guilt.

Bulstrode is philanthropic, but only when it suits his purpose, and he says as much to Lydgate. He gives the latter money to hopefully stave off suspicion, but moments earlier, refuses an ask made of need. In a sense, you get that while, to some extent, he is guilty of evil, and is knowledgeable about this fact, his flaw comes from his framing of his actions. He feels bad about what he did, but more so because of what could happen to him, either in this life or the next, than what happened to his victims. He is not incapable of compassion, but he deeply represses it.

Causobon and Bulstrode operate in similar social circles and have similar statuses, but they are both selfish, and this leads to their downfall. The other characters are perhaps callous in their actions, but they are never selfish, and this sets these two apart from the rest of the cast, apart from the minor characters. Still, the author shares to them, what they fail to grant to their compatriots. She gives them empathy.

However, there is one character that I believe was failed by the narrative, and that is Rosamund. She is characterised and intelligent and charming the first time we meet her, and after having witty banter with her brother is woven into the hearts of both Lydgate and the reader. Her thoughts of the other men in town, her high education, and her pretensions about marriage are laid out beautifully, and while we can see she does not have all the information that she may need, we empathise with her, and support her actions. Then, she gets married. After this, she acts as a hindrance to Lydgate, and while we get a glimpse into her thoughts, they are now sparse and barren. Her worst moment comes, when, after her solicitations to one of Lydgate’s rich relatives shuts the duo out of a potential source of income, after her husband had warned her not to, she breaks into tears and blames Lydgate for their collective misfortune. While he is still at fault to a degree, we get a more empathetic view of him than we do of her, which is a shame. Rosamund feels more of an obstacle and burden for Lydgate than a real person. Of course there are people who behave like her in reality, but the same can be said of Casaubon and Bulstrode, and they are very well illustrated. She also plays a part in the misunderstanding plotline between Ladislaw and Dorothea at the end of the story. These can be draining in most romance stories, but here it is over relatively quickly. Rosamund gets her redemption here, and while it makes her more sympathetic, she still is not given empathy, nor is she remorseful for her prior actions.

I do appreciate the attempt at a flawed marriage, but Rosamund is definitely not treated with the respect she deserves as a character. Lydgate is flawed too, but the empathy afforded to him makes him interesting to read, while Rosamund falls to the wayside.

One of my favorite characters outside of the main cast, Caleb Garth, is eminently likeable, charming, caring, responsible and has strong moral fibre. While he faces his own fair of challenges, mostly due to irresponsibility, he recovers from it relatively quickly, and serves as a good support for Fred and Mary when they need it. Having well written, responsible adult parental figures with no skeletons in the closet is not too prevalent in literature, and while it may not be rare, when these characters exist they usually either serve plot development in unfortunate ways or are absent from the main narrative sp It's nice to see Caleb be present in the story and not suffer for it too much. It's realistic in a way that is mundane, so not often depicted in fiction, but I appreciate his inclusion for it.

Dorothea is amazing too, and is probably my favorite character from the main cast, though I do like all of them, with Rosamund as an exception. She is kind and compassionate, and also fiery and passionate. Her idiosyncrasies are fun, and I really like how Celia, Chettam and Ladislaw all react to it. There is a lot to discuss about her and the rest of the work, which I cannot hope to do now, but one point of contention that I will cover is her ending.

In the preface and epilogue, Dorothea is compared to St. Teresa and Antigone, examples of heroic women, and is said to have the same fibre as them, but is not recognised due to the time period she occupies. I think this is representative of the treatment of women of the era, and some degree of rightful resentment towards it. Dorothea is not afforded the same opportunities as her male contemporaries, nor the extremely specific circumstances of her female forbearers. Her marriage with Ladislaw ends with him becoming an MP. This can be disappointing to readers, but I think it is a satisfactory conclusion. Dorothea is still heroic. Throughout the story she works on the development of those around her, and improves their material conditions, and despite her naivety, this is played straight, unlike the efforts of many of her literary contemporaries, such as Tolstoy’s Pierre Bezukhov. She helps Ladislaw become a better person, and it is clear that she shares a good deal of responsibility for his attributed accomplishments. The duo care for each other, and it is not implied anywhere that Ladislaw is incognizant of what she did for him. They support each other, like any duo in a good relationship, even non romantic ones should. A reader may fall into the same trap that Dorothea’s contemporaries do, where they fail to see Dorothea’s accomplishments due to the lack of attribution. Dorothea helps the world, and does not care for praise. A society that fails to do so is flawed. Still, she did good, and in life, we should hope to do good too.

Ranking

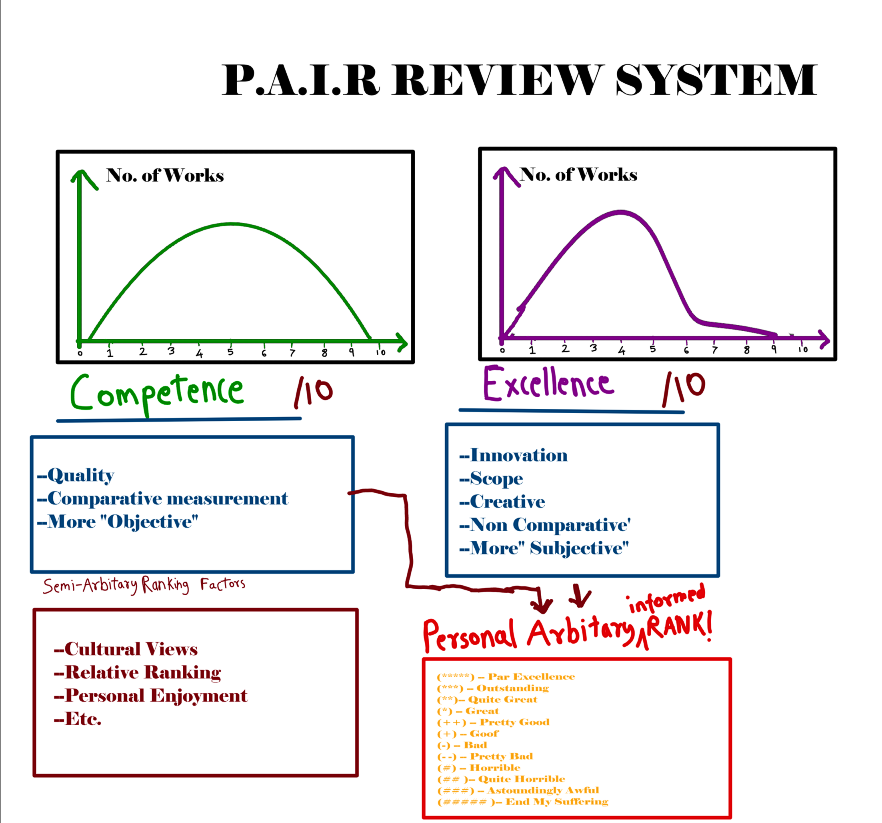

So, how does Middlemarch fare? On the C Rank, the prose is excellently written, the plot construction allows for good coverage of characters, plotlines interact with each other well, and the book is an enjoyable and not too challenging read. The coverage of Rosamund leaves something to be desired. I chose to implicate this here as it does not detract from the grandness of the work on the E . The book scores a seven on the C score.

The E rank is fun. Middlemarch deals with a large group of characters, and is ambitious in its coverage of themes, emotions and plotlines. There are many intelligently portrayed ideas, and it deals with the feelings experienced by human society well. While the location and places are simple and quaint, its deep emotional scope gives it a high E-rank. It scores an 8.

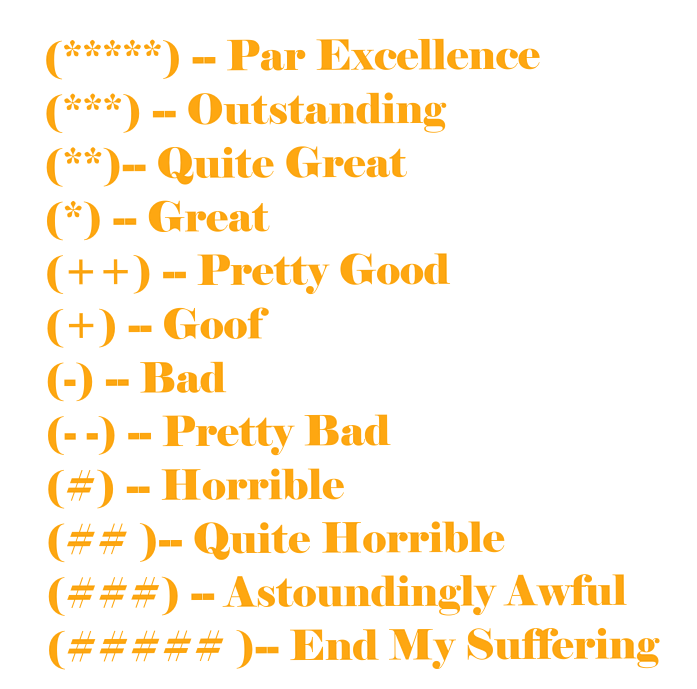

I really like this book. It speaks to the human experience, and stands out among its contemporaries in not being overly optimistic or pessimistic. It feels real, despite being enjoyable to read, and this is a much harder task than most realise. Real life is boring, yet middlemarch feels like real life and is very interesting and fun. I would consider this one of my favorite novels, and probably my favorite British novel. It scores 5 stars on PAIR. (Book rankings are fickle, and it may be de ranked soon, but it will hold 3 or 2 stars for a long time.)